19 December 1933 was a momentous day in Vizag history as the newly constructed Inner Harbour was officially opened and the news telegraphed worldwide as the largest inland harbour in the world and the greatest feat of engineering and construction in pre-Independence India

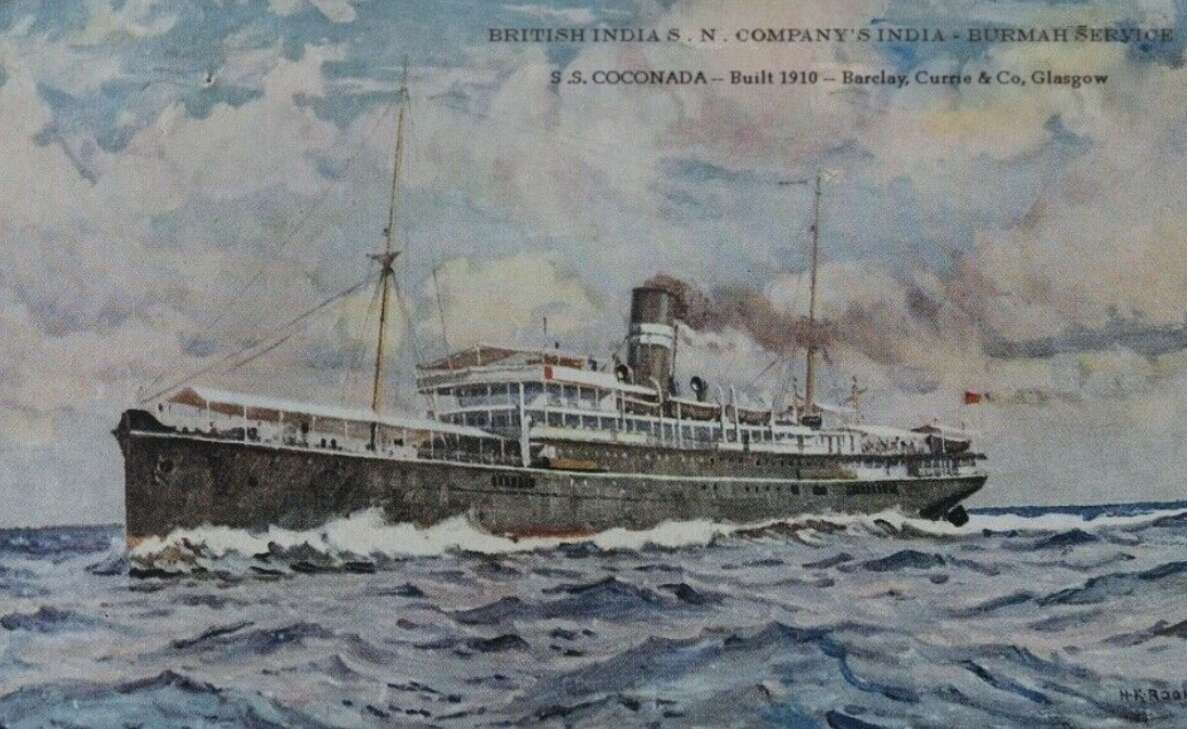

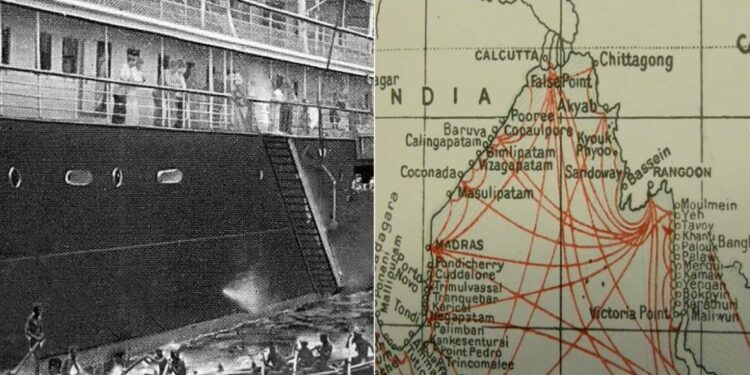

As Visakhapatnam Port commemorates 90 years since its operation, here is a special article describing the early voyages from our Vizagapatnam Harbour. This article takes you down memory lane, giving an overview of the first Voyage carried out by SS Coconada, later renamed SS Jala Durga. The vessel On 7 October 1933, Scindia Steam Navigation Company’s SS Jala Durga (Goddess of the Seas) became part of Vizag folklore when it was the first commercial vessel to enter the newly constructed inner harbour of Vizagapatam. But how much do we know about this ship’s role as SS Coconada in one of the little-known, yet great eras, of sea transportation. This was the time before World War II when there was a peak in the British India Line’s monopoly service between Rangoon and the Coromandel Coast or northeast coast of India with thousands of Indians transported to Burma every month to find work.

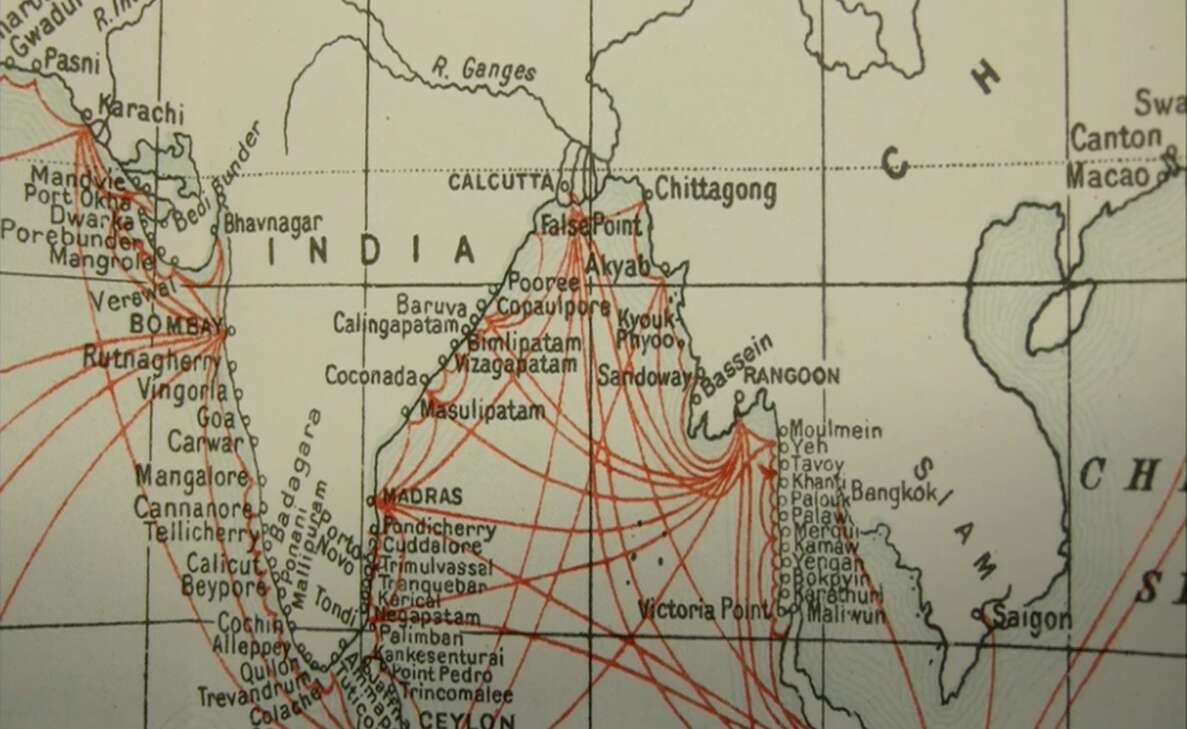

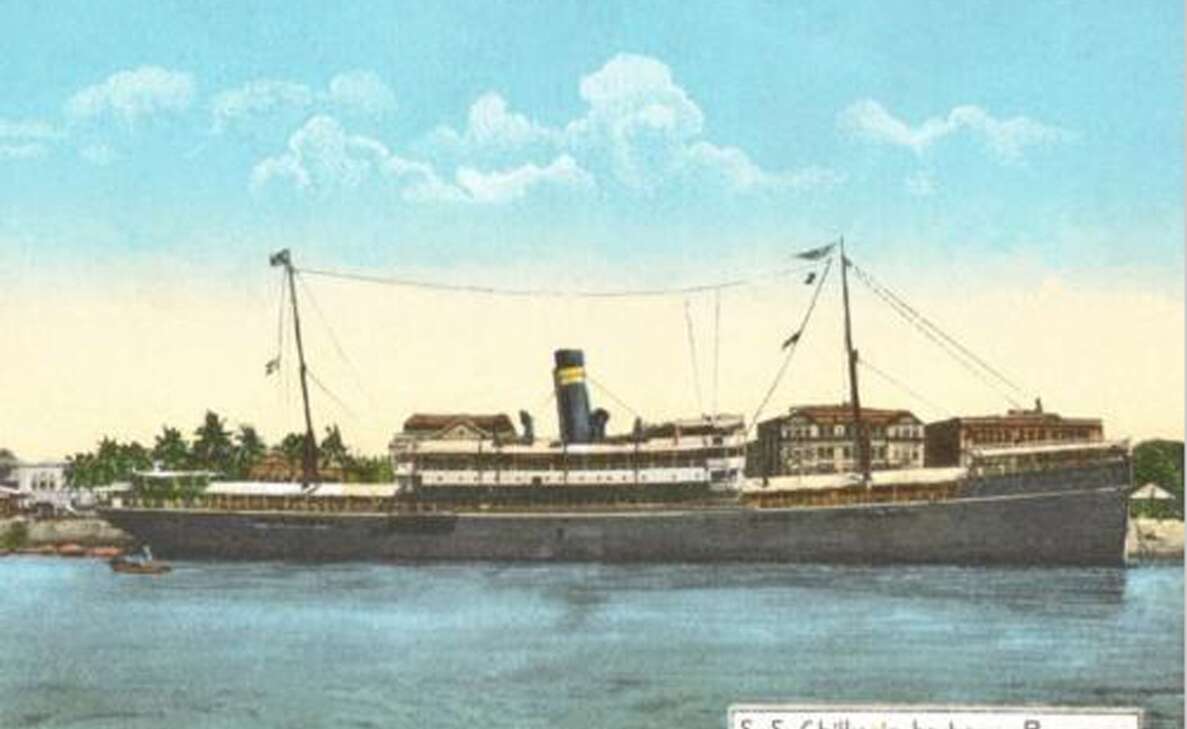

In the 1920s, two specially built ships – the British India Steam Navigation Company’s SS Coconada and the SS Chilka, carried out the India- Burma service. The ships were certified to carry up to 3760 deck passengers. At that time, for a short period, they carried more passengers than any other ship in the world. Manned by British officers and engineers with an Indian crew, there was a sailing every Wednesday throughout the year from Rangoon to Vizagapatam via Gopalpur, Baruva, Kalingapatam, Bimlipatam and Coconada, the round-trip voyage taking 11.5 days.

India’s greatest problem always has been to find employment for its millions of citizens. Right up to WWII, the provinces bordering the Coromandel Coast were able to siphon off their surplus manpower to Burma, 1000 miles (1600 Km) east across the Bay of Bengal. Burma never had sufficient manpower to garner its rich rice crops, carry out the laboring work of the cities, run its oil industry, and do the stevedoring work at the busy port of Rangoon. Not one Burmese worked as a stevedore on the ships or wharves. This gave the ‘Coringhees’, called that because they came via Coringa on the Coromandel Coast, a great opportunity. A hard-working, very reliable people, with quite a sense of humor, they became an important factor in the economic life of Burma.

The vast number of Indians who travelled were poor people classified as ‘Coolies’, who were more interested in getting to their destination as cheaply as possible, rather than in comfort. And the ships that transported them came to be known as ‘Coolie Ships’. The British government believed that the Coolies should be given every consideration, hence strict regulations were laid down regarding this type of travel and regulated that all decks be sheathed with teak. A continuous supply of fresh water was to be available 24 hours a day at a specified number of taps in each deck. A specified number of lavatories and bath stalls were to be provided on the upper deck. Furthermore, a large kitchen had to be available, with an ample supply of coal for cooking (the ships were coal-burning steamers). The passengers had to bring their food as the fare was for passage only, which they preferred. In addition, a full set of awnings with side screens had to be provided to completely cover the whole of the upper deck, fore, and aft, to keep out the rain and spray. All medical attention in the ship and the harbour of Vizagapatam had to be free.

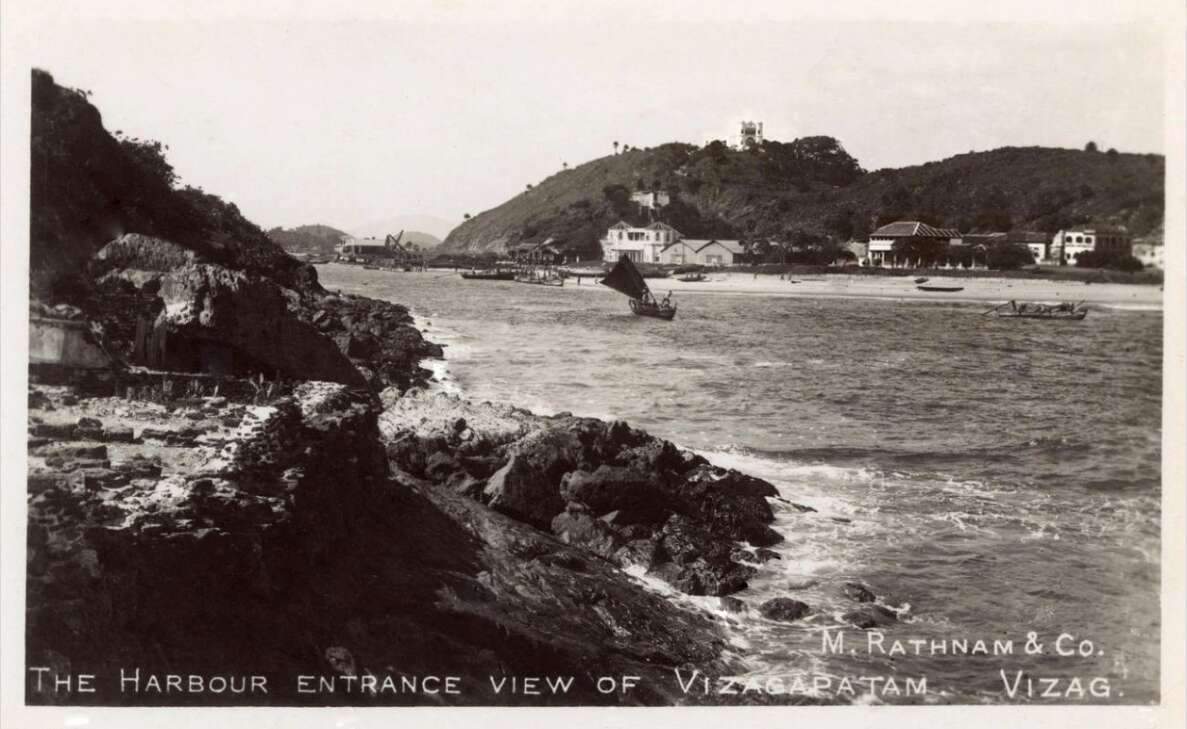

When the boarding gates were opened on embarkation in Rangoon, there was a colorful surge of chattering humanity. Passengers burdened with every conceivable type of baggage, struggling up the gangways, each in a hurry to get a good place for their homeward-bound journey. Once at sea, everything ran smoothly if the weather was good. But during the southwest monsoon, the bad weather season from mid-June to the end of September, the ship became pretty sickly. On the morning of the fourth day, fairly low-lying land would loom up right ahead with a few hills in the background. Vizagapatam, the first port, could be seen as a fairly large town with some European-style whitewashed houses and a church, temple, and mosque on its hilltops.

Steaming in towards the long straight line of sandy beach with the ever-present lines of surf, ships anchored between a quarter- and a half-mile offshore, depending on the weather. As they approached the anchorage, the fishermen would launch their Masula boats and race out to the ship. On approaching the harbour at Vizag, the harbormaster would send out a fisherman on a one-man catamaran who would wildly wave a flag to show the ship to the right berth. This was important as a safe berth had to be reserved for any deep-sea freighter that may call to load cargo.

Specially built for the work, the Masula boats were constructed for better stability, a little deeper than they were wide. Wooden poles were lashed across the gunwales in the forward end, spaced to form seats for the rowers. The steersman stood on top of the deck astern, using a similar oar to steer with, while the passengers sat between the rowers and the steersman, their baggage piled around them. Immediately, when the first boat arrived, two of its crew would jump up on the ship’s stage to assist the passengers to disembark and occasionally, there would be howls and cries from irate passengers who were in the way of the quickly descending baggage. The fishermen were not concerned – half a dozen other boats were waiting their turn.

As soon as the boat had its quota, it lost no time in shoving off. The fare for transportation by boat was included in the steamer fare. But that meant nothing to the fishermen, as they knew of a well-practiced racket, and, boarding the boat was only the start of one phase. The second commenced when the boat was well clear of the ship when the rowers would stop and politely ask the passengers for baksheesh (a tip). Of course, the passengers would refuse. A polite argument would then ensue and there is nothing fishermen loved more, particularly where money is concerned. Meanwhile, the fishermen just sat and waited and chatted and perhaps pulled a tobacco leaf out of their headbands and rolled a smoke. If the sea was at all rough, they made certain the passengers got the full benefit of it. That quickened the softening-up process.

Eventually, the arguments would become heated until the passengers turned to threats. Sometimes in the heat of the argument, fishermen would be knocked overboard. He would be hauled back wearing a big smile to continue the argument. In the end, the passengers would turn to pleading, particularly if they were becoming seasick. When they realized it was hopeless, and not until then, would they pay up. And not until the very last man had paid would the fishermen head for the shore. This racket was worked at other ports and although reported to the authorities many times, they were helpless in the matter. Should the fishermen refuse to man their boats, there was no other means of getting the passengers ashore.

To restrict the smuggling harbour of Vizagapatam, the regulations stated that no craft of any description could land on or leave the beach between 6 pm and 6 am, coinciding with sunset and sunrise which was about the same time all year. The journey was dangerous, especially the ship-to-shore transfers along the Coromandel Coast. Several mishaps were reported in the daily press. What a difference there was between the westbound and the eastbound passengers. When the latter boarded, quite a few had little more than the clothes they stood up in, plus a couple of sleeping clothes, one to lie on, the other to cover with. They also brought a few bananas, sugarcane, coconuts, and rice for cooking, enough to last them the five days to Rangoon.

Each year, it is estimated, that the two ships alone in the harbour of Vizagapatam carried a total of about 250,000 deck passengers to and from Burma on their valiant voyages.

Originally owned by the British India Steam Navigation Company, the SS Coconada along with her sister SS Chilka was built for the Coromandel Coast to Rangoon service. During World War 1, SS Coconada came under the Liner Requisition Scheme and served as an Expeditionary Force Transport. She was sold on 1 September 1933 to the Scindia Steam Navigation Company of Bombay and renamed SS Jala Durga. She recommenced the Coromandel – Rangoon Coolie Ship run under the Scindia flag on 15 September 1933. SS Jala Durga was the first commercial vessel to enter the newly opened Vizagapatam Harbour.

r of Vizagapatam on 7 October 1933. She was requisitioned once more for war duties in February of 1941 and at War’s end she operated India – Singapore – Bangkok routes, it was whilst on these voyages that she developed a leak and sank alongside the dock in Bombay in 1947. The vessel was successfully raised and repaired and continued on her normal services before being finally called to the colours’ once more when she carried Indian troops to Korea in 1953. She was finally sold for scrap in 1954.

Should you have an anecdote or history on Vizag, the author would appreciate you contacting him at [email protected]

Written by John Castellas whose family belonged to Vizag for 5 generations. Educated at St Aloysius, migrated to Melbourne, Australia in 1966, former General Manager of Engineering at Boeing & Qantas Airways, in retirement Lecturers in Aviation Management at Swinburne University and is a Vizag aficionado.

Stay tuned to Yo! Vizag website and Instagram for more such heritage articles on Vizag.

Discussion about this post