Rashtriya Ispat Nigam Limited (RINL), or Visakhapatnam Steel Plant (VSP), was established in 1982. Over the decades, RINL has witnessed a dramatic journey—from being the king of steel with over 6 million tonnes of crude steel production annually to being a debt-ridden machine, inhibited by raw material shortages, and operational inefficiencies. The journey it has gone through is nothing short of life-changing. Take a look at how this once-proud symbol of Visakhapatnam is now battling privatization and struggling to stay afloat. Here’s the untold story of RINL.

The Rise

In 1965, then-Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri envisioned India’s first shore-based steel plant in Visakhapatnam, bringing excitement to the people of Andhra Pradesh. However, the enthusiasm was short-lived, as the project was halted due to political and economic constraints when Indira Gandhi took office as Prime Minister.

The people of Andhra Pradesh fought relentlessly, leading to the birth of the “Visakha Ukku – Andhrula Hakku” movement. This widespread agitation pressured Indira Gandhi’s government to revive the plan for India’s first shore-based steel plant in Visakhapatnam. After years of rigorous planning, Rashtriya Ispat Nigam Limited (RINL) was officially incorporated on February 18, 1982, as the corporate entity of the Visakhapatnam Steel Plant (VSP), with an initial installed capacity of 3 million tonnes per annum (MTPA).

The construction phase was filled with challenges, including technological hurdles, financial constraints, and bureaucratic delays. Despite these obstacles, RINL commenced full-fledged operations in the 1992-93 fiscal year

The Rule

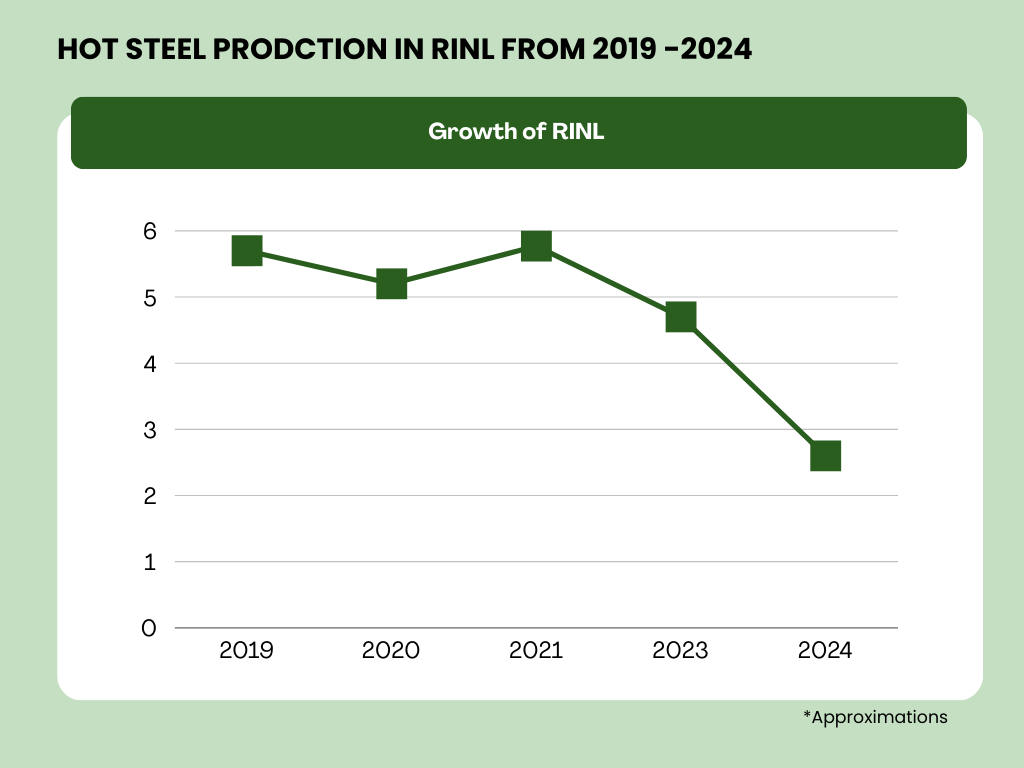

In the years following its inception, RINL expanded its production capabilities. By 2018, the company’s installed crude steel production capacity reached 6.3 million tonnes (about 4% of India’s total steel production), During the 2021-22 fiscal year, RINL achieved a hot metal production of 5.8 million tonnes and liquid steel production of 5.5 million tonnes.

To put RINL’s production into perspective:

- 6.3 million tonnes of crude steel (2018 capacity) – This is nearly twice the annual steel production of Pakistan(which is 3.5 million tonnes).

- 5.8 million tonnes of hot metal (2021-22) – That’s about 58 times the weight of the Eiffel Tower or equivalent to building over 7,500 Boeing 747 jumbo jets.

- 5.5 million tonnes of liquid steel (2021-22) – That’s enough to manufacture over 1 billion stainless steel kitchen knives or nearly 100 million cars, considering an average car requires about 55 kg of steel.

The Rust

While RINL experienced periods of profitability, its financial performance has been inconsistent. Between 1991-92 and 2020-21, the company reported profits in only 15 out of 30 years. Notably, in the 2021-22 fiscal year, RINL recorded a turnover of ₹28,215 crore, marking its highest to date. However, this figure declined by 19% to ₹22,778 crore in 2022-23.

Several factors have contributed to RINL’s recent decline:

- Financial Strain from Expansion: Post-modernization and expansion efforts led to significant debt, with loans taken from banks becoming a financial burden.

- Production Challenges: By mid-2024, production had sharply decreased to approximately 2.5 million tonnes per annum, down from a capacity of 7.5 million tonnes. This reduction was due to the closure of two blast furnaces, primarily caused by a shortage of coking coal.

- Financial Losses: The plant reported losses of ₹2,858.74 crore in 2022-23, which escalated to ₹4,848.86 crore in 2023-24.

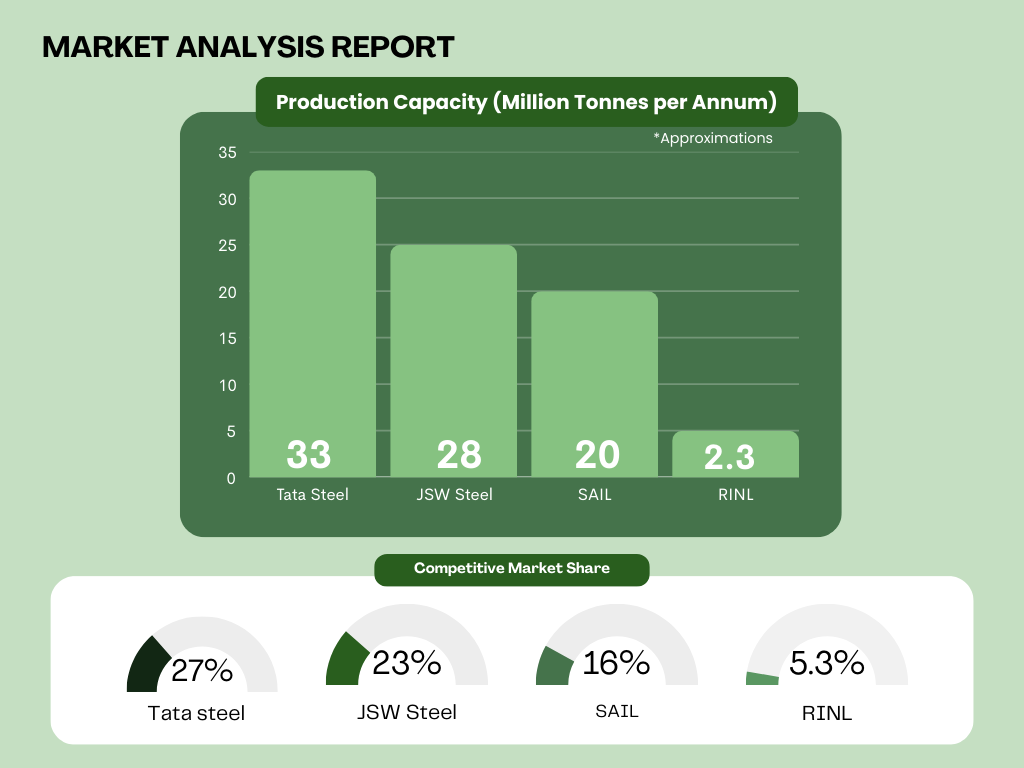

- Increase in Public Companies

The rapid expansion of Tata Steel and JSW Steel has overshadowed RINL, raw material shortages, and high costs. Lacking captive iron ore mines, RINL faces rising production costs, losing market share to private giants. Without urgent reforms, its decline seems inevitable.

The Possible Revival

Amid these mounting challenges, the Indian government approved a financial package of ₹11,440 crore in January 2025. This infusion aims to address the plant’s financial woes and includes ₹10,300 crore as equity capital and the conversion of ₹1,140 crore of working capital loans into non-cumulative preference shares.

Despite these efforts, concerns about the plant’s long-term viability persist. Discussions around privatization and the need for strategic partnerships continue as stakeholders seek sustainable solutions for RINL’s future. RINL’s journey reflects the complexities of managing large-scale public sector enterprises in a dynamic economic environment. Balancing expansion ambitions with financial discipline remains a critical lesson from the Visakhapatnam Steel Plant’s experience.

RINL has played a crucial part in the growth and prosperity of our city. With its currently fluctuating state, what holds next for Vizag? Explore the possibilities in this article about the future of Vizag.

If you enjoyed this untold story of RINL then Stay tuned to Yo! Vizag’s website and Instagram for more related articles.

Discussion about this post