Click-clack – the weaver pulls the batten, works his way on the loom as the legs pedal in tandem. There is an unnoticed rhythm in the movements. It is fascinating to see taut threads gradually converge into a beautiful sari on the beam. Andhra Pradesh, being home to many rich and vibrant clusters of handloom societies, is a treasure trove of several stunning weaves. Rajeshwari Mavvuri, a handloom and handicraft enthusiast from Vizag, is here with us yet again to take us on a trip to Venkatagiri in Nellore district and share interesting stories behind the making of these unique saris.

Notwithstanding its glorious past, how many people from the Telugu-speaking states know about the significance of this weave? Textiles of Venkatagiri were once patronised by the kings and the queens. And today, we don’t even talk, let alone celebrate the exquisite GI tag that the weave rightfully earned. Venkatagiri is Andhra’s best-kept secret.

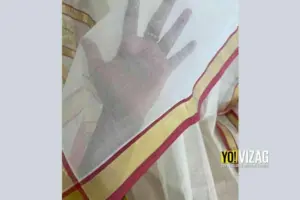

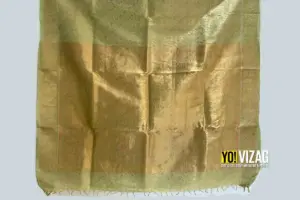

Venkatagiri juxtaposes the coveted hills of Tirupati. The town is situated in an important cotton-growing belt that produces fine and sheer cotton muslins. The weave was a darling of the Nizams and other kings that ruled the Andhra region. Royals preferred Venkatagiri to other weaves because of its finesse that is achieved by high thread count. Moreover, artisans took pride in using real zari to weave the border and the pallu of a sari, and coveted gold-bordered in case of turbans and dhotis.

During the eighteenth century, the kings of the Asaf Jahi dynasty promulgated acts that attracted textile craftsmen from the central and western regions of India to the Andhra region. Naturally, it resulted in the osmosis of ideas and techniques from other weaving clusters. It was said that the Zamindars and other royal families of Andhra had weavers that would work only for the clan. This arrangement ensured the motifs remained confidential and exclusive.

Back in the day, Venkatagiri saris were unbleached, strikingly resembling kasavu sarees of Kerala. Ever since, the handspun fabric Venkatagiri has always been cherished by the upper strata of society. Over the years, Venkatagiri’s fine cotton muslin jamdanis were exported to Bengal and Chanderi. The trade lasted until the end of the nineteenth century. Sadly, during the first half-century of the 20th century, the quality of the muslins from regions of Bengal and Chanderi has continued to decline, leaving ripples that lasted longer than usual.

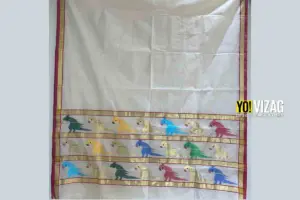

In recent years, artificers of Venkatagiri started to push the envelope by weaving an extra weft to the body and a pallu of the sari. Commentators say that this was done in response to the competition from the clusters such as Uppada that use the jamdani technique on fine cotton. Despite the legacy and innovation, the weavers of Venkatagiri face a threat from entities that mass-produced cheap power loom saris.

Today, only a handful of saris are richly brocaded with motifs in gold. While other regular saris sport a plain body with a pure kaddi zari border. Nevertheless, due to the extensive craftsmanship involved, a typical cotton sari from the house of Venkatagiri costs as much, if not higher than their silk counterparts, thus making Venkatagiri the finest among the plain cotton textures the world over.

Number of weavers to weave a sari: One or two depending on the complexity

Number of days to weave a sari: 3-90 days depending on the complexity

Technique: Jamdani

Type of Loom: Pit loom

Specialty: Very fine cotton with pure cotton zari

Field/Body: Plain, occasional buttas

Border: Kaddi zari border

Motifs: Flowers, paisleys, circles

About the Author: Rajeswari Mavuri is an active member of the Crafts Council of Andhra Pradesh. She endeavours to make a difference to the Indian art and artisans alike. She is just a message away on Instagram: @rajeswarimavuri

Discussion about this post