The history of Vizag has always been associated with ancient British establishments, stories of how it turned into a metropolitan from an undisturbed coastal city, and the emergence as one of the major ports in the country. But can you imagine the City of Destiny being war-struck? Back in 1942, an air raid was conducted by the Japanese off the coast of Vizag. Fortunately, the effect of the Japanese air raid never made landfall on Vizag.

John Castellas, a Vizag heritage enthusiast and aficionado, shares the story of how Vizagapatam was on the verge of war.

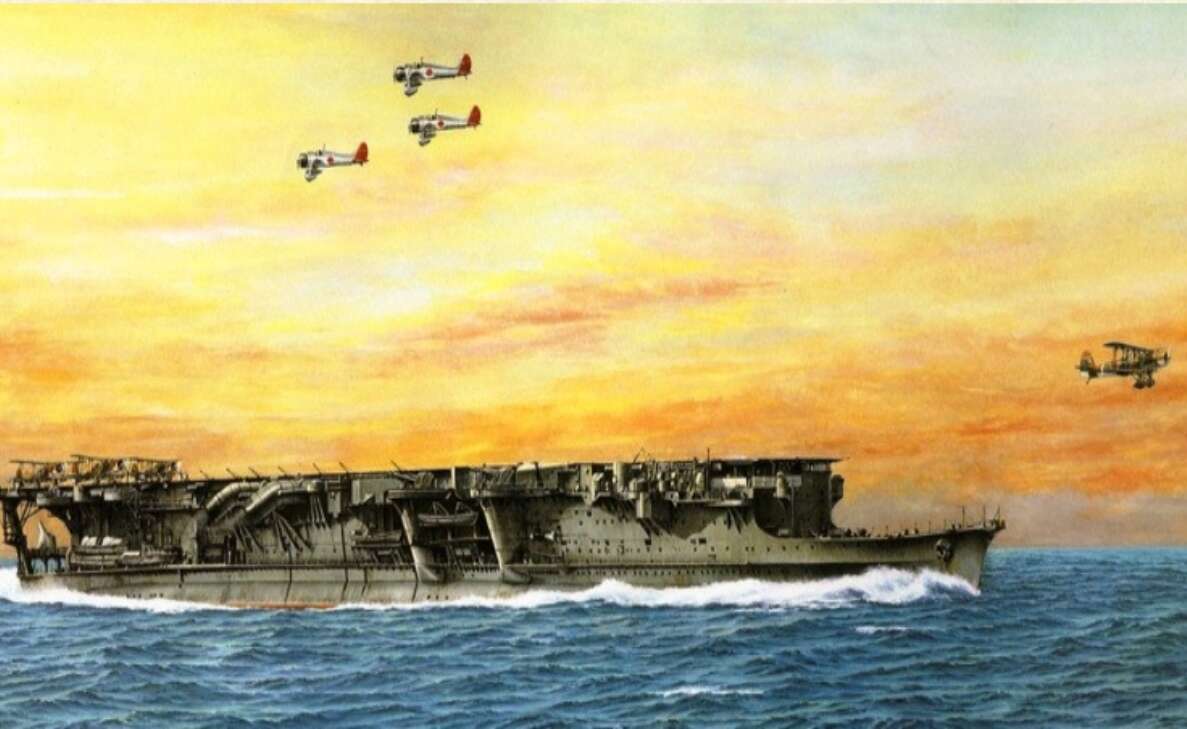

For the better part of World War II, to Vizag folk, the war in Europe may have been far away, but in 1942, the citizens of Vizag faced the terror of war when, on April 6, Japanese Kate Bombers from the carrier INS Ryujo launched an air raid. The main target of the raid appeared to be the new harbour, the new Scindia shipyard, the powerhouse and the steamers in port.

The reality of Civil Defence was upon Vizag and people learnt to cope with a different way of life. Censorship, rumours, blackouts, rationing, air raid precautions, military recruitment, gun emplacements, troop movements, and military aircraft became the norm.

Civil Defence Headquarters was established at Hawa Mahal on Beach Road and the Collector led the planning for the town’s war readiness. The war in Burma and the Malay peninsular was anticipated to result in heavy casualties and injured soldiers were to be repatriated to makeshift military hospitals at Andhra University and St Joseph’s Convent in Waltair. The university was moved to Guntur for the duration of the war. Most of the nuns and girls of St Joseph’s and boys at St Aloysius were relocated to Jeypore whereas final year High School boys and girls stayed at St Aloysius.

Censorship of any public announcements didn’t last long as refugees from Burma who had trekked to Assam had started to arrive, and came with stories of the Japanese invasion. Tokyo Rose was the feminine voice of propaganda English broadcasts from Japan warning of an invasion. Vizag was scared that an invasion force could land on its beaches. Blackouts were issued for the nights. Defence of India Act made the Beach Road a prohibited area between the lighting-up time and sunrise and anyone found there after sunset, which ironically included fishermen, was fined. Sea-facing Pillbox gun emplacements were constructed; public buildings were vacated for the shelter of people to hide after air raid warnings were given. The lights on the roads were fully extinguished. Glass windows had to be removed. Trees were not supposed to be cut. To hide the town of Vizag from Japanese bombers and an impending air raid seemed the primary motive. In the midst of all this, the city resorted to a well-practised pastime of rumour-mongering. It was reported that:‘The railways were practically paralyzed and all the subordinate staff and labour fled from the place…every jatka and goodu bundi was employed by Vizag’s population in a long road train inland to Waltair and Vizianagram. All local shops were closed and practically everyone fled the town. The port employees fled, the labour at the Scindia shipyard fled, as did the coolies employed on the construction of the aerodrome.’

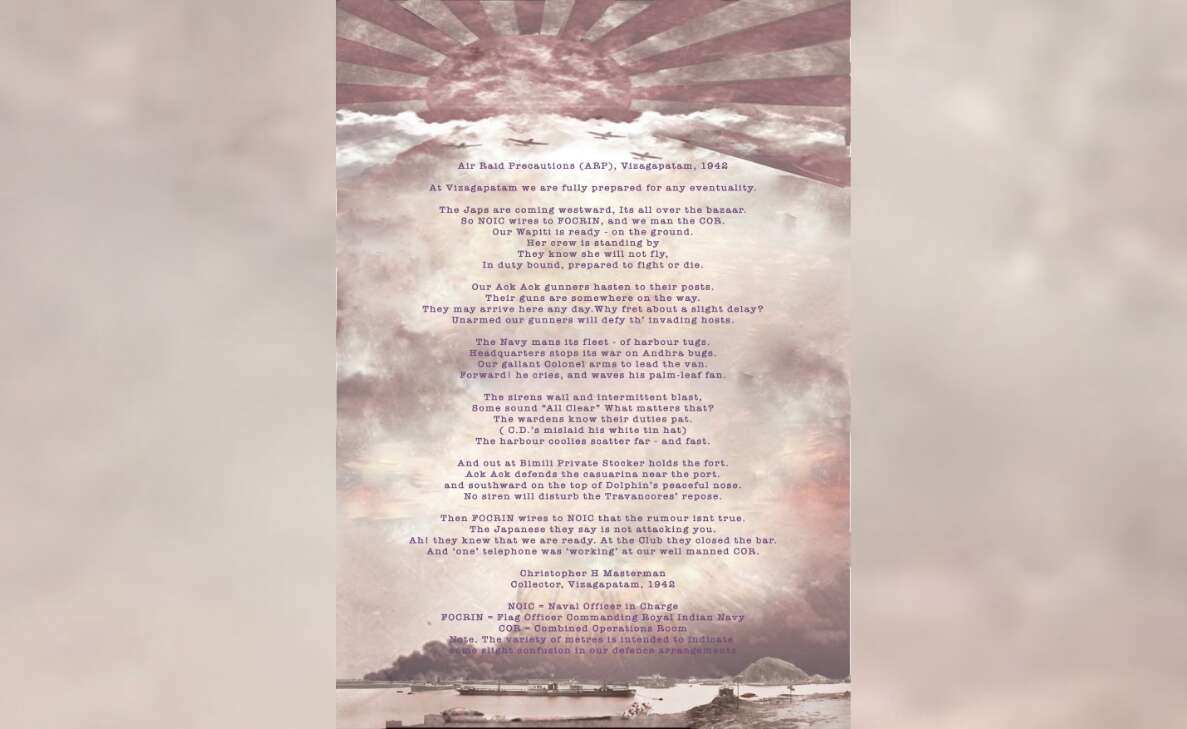

The Collector of that time (1939 – 1942) was Christopher Masterman who led the Civil Defence preparations for the town. He penned a light-hearted poem on the war readiness of Vizag before there was an actual air raid by the Japanese.

By the summer of 1942, there was a scarcity of food and other essentials. Food and textile prices went up; both were issued to civilians by a quota on ration cards. Purchases were limited to Rs 5 per person. If there were a good thing people learned during that time, it was to be economical. Thrifty ladies invented several recipes to make use of leftover food. With Burma under attack and shipping lines targeted by Japanese torpedoes, rice – the staple food of the Madras Presidency – became scarce. Idlis and dosas were being taken off the menus of most hotels. Idlis – the staple dish for many – became scarce with strong rumours that the government would ban the food item. Wheat was being imported as well as being moved in from the north. But the food tastes of people were not very easy to change. Free cooking demonstrations of wheat dishes were given at street corners. Rava idli and wheat dosas were invented during this period. The government categorised weddings as a major usage of food and restricted wedding invitation lists to 30 people. The organisers had to advertise to guests not to turn up for weddings.

Every type of home need like firewood, paper, soap, kerosene and sugar was in short supply. Even matchboxes were rationed. Leather was redirected for soldiers’ footwear and rubber was needed for the war effort, so bicycle tyres were scarce. The few cars found gasoline hard to get. War was a glutton for metal resulting in scarcity of some metals. Wiring for radios and planes, casings for bullets and bombs to stop them from fouling – all of these were made of copper. Unfortunately, more copper was in the coins circulating in the market than in the inoperable mines. So, people realised that the intrinsic value of the coin was higher than its notional value (six annas of copper were in a four-anna coin). This led to a large-scale hoarding of coins and a shrinking of trade. The only source of coins was the State Bank as shopkeepers refused notes and disliked giving change. The government, unable to crack down on the coin hoarding, introduced the coin with a hole in the middle.

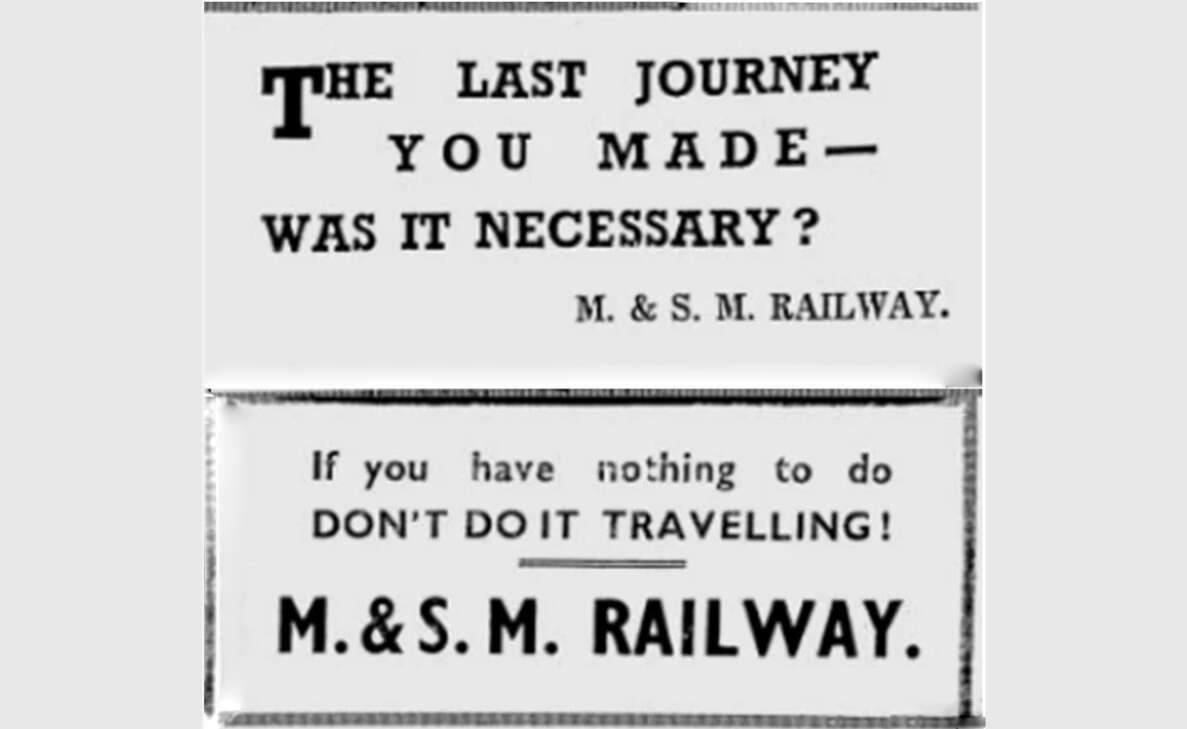

Scheduled railway services between Madras, Waltair and Calcutta were limited. The railways advertised asking people not to travel. “The last journey you made – was it necessary?” asked an advertisement for the M&SM (Madras and Southern Mahratta Railway) railway. Most of the railway capacity went to troop movements for the many army, navy and airforce bases along India’s East Coast.

The cinema industry suffered mainly because the world’s largest raw celluloid film manufacturers were in Germany and Japan, and they were at war with Britain. In 1943, the government imposed a raw stock film control and ruled that no cinema film should exceed 11,000 feet (the average length of a Telugu talkie, sometimes dubbed in Tamil, at the time was about 20,000 feet with songs). Telugu films were being made in Hyderabad mainly by Gemini Talkies. The first female playback song was recorded for ‘Bhakta Potana’ (1942).

Directors struggled with the craft of telling a story crisply or without too many songs. The war period produced lesser talkies with fewer songs and the unwritten restriction that heroes had to be good singers also faded. It laid the line for actors proficient at other aspects, like stunt scenes and oration, to become heroes. NTR and Sivaji Ganesan found their feet post-war.

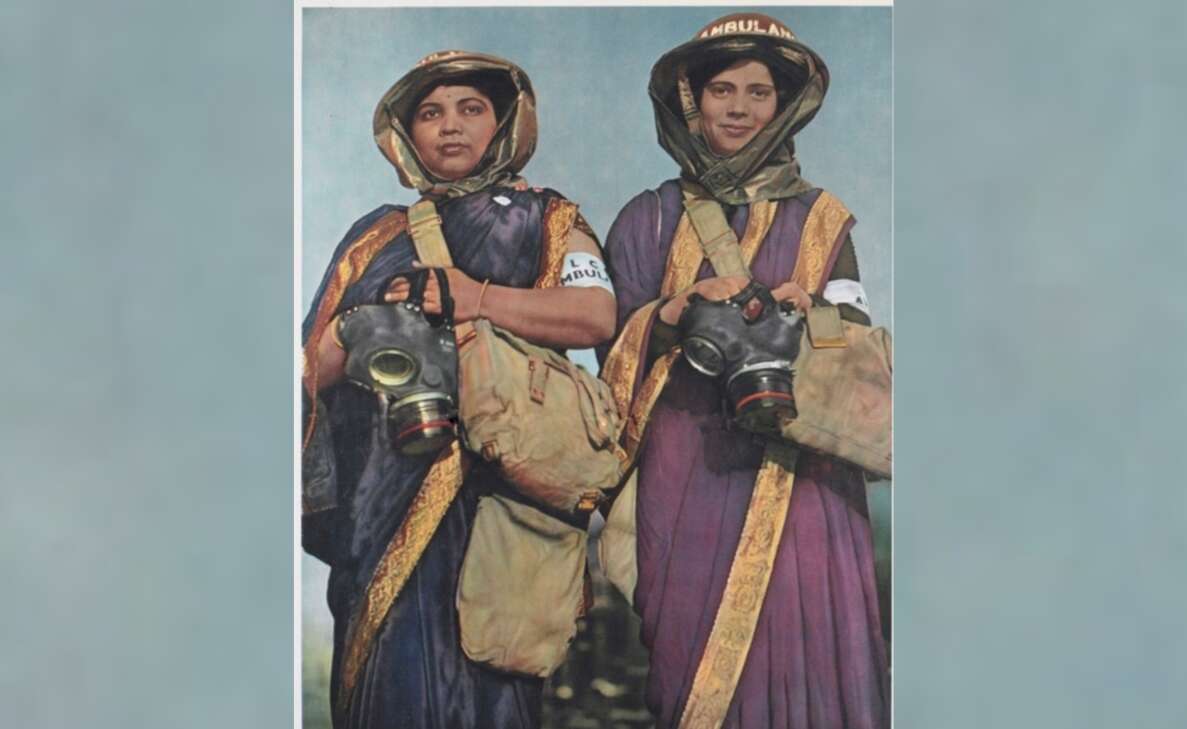

The Women’s Auxiliary Corps (India) was formed in March 1942 for the duration of the war. Their main tasks were cypher clerks, wireless operators, telephone and typewriting, First Aid, Air Raid Protection, driving vehicles and managing delivery of essential services. A local member, Sergeant Major Sybil Brett, recalled the contingent assembling at the old Vizag lighthouse and marching to duty down the Beach Road to the Hawa Mahal HQ each morning. Miss Dorothy Pollock from Vizag joined the WAC(I) in Vizag and was a cypher clerk in the Intelligence Branch in Delhi when she deciphered the coded message from Winston Churchill that Germany had surrendered and the war in Europe was over. The WAC(I) was disbanded on India’s Independence in August 1947.

Regular war fund collection was an irritant. Money was collected in Vizag by raffles and fetes to buy planes for the RAF (Royal Air Force). The aircraft were dedicated to the Madras Presidency Squadron. There were Spitfires misspelt as Vizagputum II and also a Wellington Bomber named Vizagapatam.

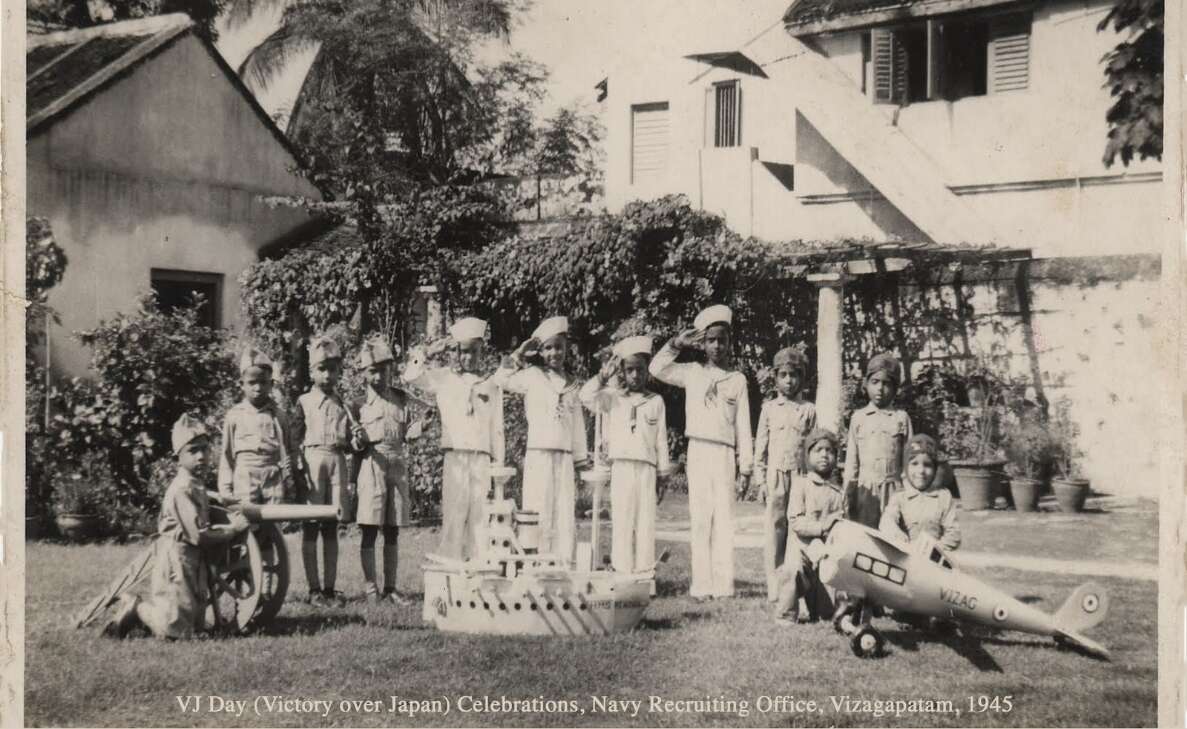

On 15 August 1945, when Japan surrendered, Victory Japan or VJ Day was celebrated. Collector HH Charleston took the salute at the Collector’s Office during the victory march past. The people were relieved and special pujas were done in the temples of Vizag. At the East Coast Battalion Club in Vizag, a children’s tea party was held. Ironically, it was the 15 August, two years later, that India was Independent.

World War 2 marked a chapter in the history of Vizag. Many a Vizag family had a member in the armed forces. In addition to the Port employees who lost their lives in the bombing of Vizag, some families lost members in the conflict in far-flung corners of the globe. The war left Vizags’ residents deeply seared by fate’s unkindness as a faraway war changed their lifestyles for many long years.

Written by John Castellas whose family belonged to Vizag for 5 generations. Educated at St Aloysius, migrated to Melbourne, Australia in 1966, former General Manager of Engineering at Boeing & Qantas Airways, in retirement Lecturers in Aviation Management at Swinburne University and is a Vizag aficionado.

Stay tuned to Yo! Vizag website and Instagram for heritage stories.

Discussion about this post